NO BOOK CLUB DECEMBER

Previous Book Picks

Previous Book Picks

Out of Print Newsletter August 2020

Our newsletter Out of Print features original artwork from writers in the free world and from our incarcerated book club members. As a $10 monthly Patreon subscriber, you’ll get your own copy in the mail!

Download August 2020 Edition

Subscribe on Patreon

Older issues:

April 2020

August 2020 Contents

Editor’s Note

Unreading Colonial Food Systems

In A Pandemic, Prison Abolition Is Necessary And More Possible Than Ever

Infographics: U.S. Prison Statistics

VOICES OF DBI CAPTIVES: Mission Statement

VOICES OF DBI CAPTIVES: Understanding my Childhood Traumas

Illustrations by bbyanarchists

Editor's Note

This edition was scheduled for a May release. We were admittedly behind with the artwork as it was still a strange time, as far as creative work was concerned. The written pieces however, were completed shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 lockdown. Naturally, as the world was turned on its head with the events of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, our attention moved to the immediate needs of the streets and our communities. Similarly, being mindful of the energy and emotional strain of recent times, not all the commissioned artwork could be completed, understandably so. We are distributing this edition without all of the intended artwork, but wholly understanding that the words in here still ring true and are worth sharing.

The times are ripe with change. The consciousness is both absorbing and shifting. The movement for liberation is gaining new curious minds. And those who have been putting in the work are poised for leading the way to knowledge. As this is happening, be sure to tap in with your local organizations, if you haven’t already, and see where they need a hand. Monetary giving is important, sure, but so is our collective energy, our physical presence, our minds, our voices, our access, and our resources. The movement will ebb and flow, but the momentum will only grow with your participation.

The organization and the tactics some are calling for are being worked out as we speak. And remember these organizers are no different than you or anyone else. They believe strongly enough to jump in and mobilize their community. And if you have thoughts concerning how things should be done, you need to be on the ground and in the action. All the theory in the world is useless without real-world practice. Your ideas will shift as you learn to navigate the ever-changing forces seeking to silence us. The machine within which we exist excels at co-opting and undermining the movement. So, it’s imperative to stay vigilant.

If it is unclear what we’re aligned with, let it be known, in an effort to undo the number of atrocities carried out by white supremacist capitalism and to imagine new safe spaces for existence, we’re centering our liberation to be in alignment with the indigenous communities, the black trans and non-binary communities, and black women and femmes. We need to dismantle the patriarchal social contract that governs us and re-imagine a future much different than the one in which we find ourselves. To that end, it’s fuck the police, let’s abolish them and prisons and the carceral state of punishment, raise the standards of living to include universal healthcare, access to housing and nutritious food, and create an education system that centers on critical thought, all while moving away from a system centered on capital and exploitation.

Unreading Colonial Food Systems

by maya burke (mutooro)

Like many people who went through U.S. public school systems, I am intimately familiar with institutional food; canned vegetables, square cut pizza, frozen & highly processed mystery meats, syrupy fruit cups, all of that. Institutional food is low-cost, low in nutritional value, and arguably pretty gross. I remember asking our school superintendent why our cafeteria wasn’t able to purchase food from the vibrant community of local farmers. He told me that our school was bound up in a large multi-year contract with a number of other schools, and that because of this contract we had to buy food from certain distribution companies.There were also a number of other financial and health code reasons that essentially prevented our school from sourcing our food from small local farmers. I heard this gesturing towards a world of contracts and laws and budgets that I did not understand, but I was still unconvinced. Seemed like a scam to me.

Eating at home and in restaurants have always been pretty weird experiences for me too, as these were usually just arenas for dysfunctional family dynamics to play themselves out. A lot of meals alone as well. All in all, my relationship with food and eating has been pretty terrible for most of my life. My eating started to become disordered in many ways, and things didn’t start to shift until I began gardening and learning more about the complexities of the industrial food system.

It started to confuse me that so much of our popular and mass media is silent on very concerning issues in food production and distribution in what is currently known as the "united states." We all eat, we all engage with the intricate network of stores and distributors and growers and land holders in some way. While learning more about the industrial food system started to alleviate some of my previous confusion, it also brought its own heaviness. And as I studied Indigenous and Black resistance to colonial violence, food sovereignty became increasingly central to my understanding of historical and contemporary social issues. I became presciently aware of these complex networks everytime I ate something that wasn’t grown or produced locally to me (which was pretty much all the time.) Often I’d gag or cry or get really anxious. I began to dread eating, or would binge eat easy to consume junk foods. It all felt so hard and horrible.

Fully engaging with historical and contemporary realities of industrial agriculture and colonial violence can be strenuous, painful, triggering, guilt inducing, and/or just plain exhausting. And making active connections to the food we eat every day can be a stressful and nauseating practice, but I believe that it is necessary to do this. I believe that it is necessary to not look away, that it is necessary to actively recover and heal our relationship to our food sources.

I. FOOD PRODUCTION IS BROKEN & UNSUSTAINABLE

Our nourishment, food systems, and working lives are largely in the hands of white supremacist corporations and militarist governments. Our food production systems are mechanized, as well as toxic to our biology and to our environments. The majority of people living in urban, peri-urban, and suburban places in industrialized countries have little to no relationship with where their food originates. Most folks' relationship with their food stops with the grocery store or restaurant. Behind the grocery store is a massively complicated system of food production and distribution that is violently extractive. This massive network of operations that make-up the globalized industrial agriculture system is disastrously damaging to planetary ecologies, and is exploitative by design. And although there are more than 300,000 known edible plants on earth, most of the world’s population is largely reliant on twelve types of grains and twenty-three species of vegetables. This collapse in human dietary diversity is parallel to the mass extinction episode of the current epoch that is being rapidly intensified by corporate fossil fuel usage, pesticide and chemical fertilizer contamination of ecosystems, and clear-cutting forests for timber, monoculture operations, and highly concentrated livestock production.

To the dismay of life on Earth, intense investments in genetic engineering, globalized food distribution mechanisms, and ‘smart farming’ technology are central to the industrial food systems that bring food to an ever-increasing population of people who live in urban environments separated from la via campesina (the peasant way). Indigenous food systems and life ways are destroyed to make way for the expansion of western imperialist consumerism. Our labor systems and ways of life have been almost totally geared towards industrial means of production and capitalist profit accumulation. This profit-centered, industrial status quo is not sustainable, and was never designed to be sustainable. We need to reckon with this collectively and work to recover relationships with the ecosystems that have sustained us for thousands of years.

II. WORKERS HAVE LITTLE TO NO PROTECTION

Enslaving plantation economies are the foundations of modern industrial agriculture, so the exploitation of workers is designed into the fabric of our labor structures. Systems with genoicde and enslavement at their inception cannot be reformed, and industrial agriculture and colonial projects continue to exploit humans, non-human animals, plants, and entire ecosystems. Industrial agriculture systems are not only flawed and damaging to the environment, they are particularly exploitative of workers all along the industrial chain: field hands, food packers, truck drivers, gas station workers, grocery store workers, restaurant workers, factory workers that produce tools, chemicals, packaging etc. These are occupations that in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic have been deemed “essential,” but are otherwise relegated to low wage, “unskilled” and expendable occupations.

Food service workers are chronically under-paid and exploited. States have varying minimum wages for agricultural and food service workers with the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour. Agricultural workers in the "united states" are largely economic, political and climate refugees from Central and South America working within a U.S. agricultural framework that is founded on the history of African enslavement and forced labor. After the formal “end” of enslavement in the "united states," there was a populist movement in the early 1900s for labor protections. Two classes of occupations were left out of these labor protections, forwarded by then President Woodrow Wilson. These occupational classes were domestic and agricultural labor. Agricultural workers found some labor protections as a result of the United Farm Workers movement, which still explicitly excluded undocumented workers from the movement, but resulted in a number of changes in federal jurisprudence. These protections, while still highly limited in scope with the continued capacity for labor exploitations, are at the very least extant. Occupational protections for Domestic Workers have yet to be formalized on the federal level.These occupational classes were strategically omitted from the original labor bills of the early 1900s, specifically because they were occupations mostly held by formerly enslaved Black people. This is just one of the persisting legacies of enslavement that are playing out in the contemporary material conditions of American society.

III. SUSTAINABILITY, OR LACK THEREOF

Industrial food systems were never designed to be sustainable, or even nourishing. They are designed for profit. The complex network of growers, distributors, and merchants is also seriously undergirded by the fossil fuel industry. Industrial agriculture demands immense fuel inputs for growing, for transportation of goods, and for the transportation it takes for you to get to the market or the grocery store. The "united states" is linked by a network of interstate highways, and strategically so. Numerous efforts of maintaining and establishing public transit networks have been intentionally sabotaged by vested interests in the fossil fuel industrial complex. The National Interstate and Defense Highways Act forwarded by president Dwight Eisenhower was signed into law in 1956. This was a huge action in tandem with the interests of the fossil fuel industry. Today the majority of households are dependent on individual vehicles for transport to and from places of work, education, and food and supply distribution centers. Concurrently, large truck-loads of food in bulk quantities are shipped between distribution centers all over the nation, hemisphere, and globe. The fuel inputs for this alone account for a large portion if not a majority of fossil fuel consumption.

At the agricultural sites themselves we see industrial, factory-like conditions with the rearing of crops and livestock. These industrial farms employ horrifically toxic practices to reap high yields at low fiscal costs, with sky high environmental and human health costs. These practices range from planting genetically modified crops, using toxic chemicals to deter weeds and pests, and keeping livestock animals in abhorrent conditions. Petroleum, gasoline, ethanol fuel, plastics, and petroleum based chemicals are used at almost every stop along the chain. As we observe increasingly drastic changes in the planetary system as a result of industrial waste, and the need for sustainable practices and products intensifies, it is imperative to critically disengage from the globalized industrial food system and re-localize our food webs as a way to reduce fossil fuel usage and dependency.

IV. “YOUR” PROPERTY ISN’T YOURS: native land is not a commodity

Anti-Black and anti-Indigenous violence are complex processes of oppression that structure and actively perpeutate white supremacist domination of native lands. To discuss the importance of liberation from exploitative racialized capitalism and industrial agriculture, we must acknowledge the context of the western hemisphere as a system of anti-Black settler colonial structures on stolen indigenous land. This context must always be stated in any and all conversations about liberation from exploitative racial capitalism and industrial agriculture.

Throughout time, space, and ethnic background, native peoples have resisted and contested the commodification and privatization of land. We live trapped within systems centered on private property and exploitative profit making. While many landlords, homeowners, real estate magnates, and industrial farmers possess titles and deeds to plots of land, it is imperative to internalize the wisdom of indgenous and folk peoples that land cannot truly be possessed. The enforcement of commodifying logics onto the natural world is a manifestation of domination. Mountains, rivers, forests—the living ecosystems that sustain us—do not recognize man-made boundaries of property, or the desecration of life and land into commodities.

98% of all of the private rural land in amerikkka is owned by white people. One stereotypical image of a farmer in the amerikkkan public consciousness entails a white middle-aged man from the Midwest on a tractor. This is a false normative image perpetuated in white supremacist society, but is a realistic image of who is currently stewarding much of our food sources. This is a white-washing of food and land work on this continent, where Indigneous peoples have been stewarding ecosystems for tens of thousands of years, and Black and non-Black POC have been farming and resisting displacement for generations. White supremacist industrialist society currently and almost totally determines the conditions of food access, security, and sovereignty. Most people now exist disconnected from their own food sources and, at the whim of big agriculture, are subsisting on the secretions of its mechanical churning.

The violence of settler colonial society has always been centrally about food systems, food sovereignty, and land sovereignty. And the failures of the colonial industrial food system have been apparent to those on the frontlines for centuries. The COVID-19 pandemic is perhaps bringing these shortcomings to light in a way that is more accessible to the mainstream consumer public. Food insecurity is being experienced on extremely large scales, especially in low-income urban communities where people have little to no access to land and are disconnected from agricultural knowledge. The obstacles to nutrition access are exacerbated by unemployment and limited funds to purchase groceries.

With food and economic systems collapsing amidst the COVID-19 outbreak, state governments have implemented various levels of recommendations and directives for the halting of non-essential activities and occupations. How have food service and food service adjacent workers all of a sudden been deemed essential in a context that is actually degrading and materially exploitative of their labor? These markers of essential and non-essential are deeper than the contemporary COVID-19 context. To unpack these dynamics around food, food work, and service economies, it is helpful to take on land and food sovereignty as lenses with which to view "united states" history and liberation from exploitation.

V. LA VIA CAMPESINA

Peasants, Black folk, Indigenous land stewards, migrant farm workers, and fisher folk are on the front lines of the struggle against state and corporate sponsored terrorism, natural resource extraction, environmental destruction, occupation, gentrification, and police/paramilitary violence. In many cases, comrades all over the world are winning these battles against their oppressors, but not without loss of life and almost constant struggle. Environmental activists, abolitionists, land and water protectors, and peasants are often surveilled, targeted, and murdered by government or corporate backed forces. Food sovereignty is at the center of these struggles, as healthy and financially accessible food nourishes global resistance movements.

We see the continual effects of colonial violence and extractive degradation as Indigenous folks experience and resist ongoing desecration of their ancestral homelands, and Black folks are continually displaced and struggle to access housing in urban hoods, and farmland in rural areas all over the country. As this plays out, there is an ever-increasing urgency for black reparations for the legacy of enslavement and land justice for Indigenous peoples.

There is also an ever-increasing urgency for revolutionaries inside of amerikkka to recognize and take direction from those Indigenous and Afro-descendant peasants struggling for land, food, housing and water within and beyond amerikkka. All over the globe, there are organized people and social movements actively resisting this system by constructing local food sovereignty in their communities. The formation of La Via Campesina in 1993 has unified peasants on a global scale. From the Union of Agricultural Work Committees in the ancient olive orchards of Palestine’s West Bank, westward to the autonomously governed socialist communes of Caracas Venezuela, southward to the Afro-Brazilian fishing favela of Gamboa De Baixo, eastward to the Indonesian Peasant Union.

Peasants produce 70% of the world’s food on 25% of the resources. 70% of peasants globally are women. As of now, 250 million peasants have been organized into the world’s largest non-secular social movement through the peasant federation of “La Via Campesina.” The peasant food web conserves much of the world’s biodiversity. Peasants also do this work with significantly less control and sovereignty over land than large private entities or state governments. Largely and unfortunately, this information is unknown to the general public in the so-called "united states."

Peasants produce 70% of the world’s food on 25% of the resources. 70% of peasants globally are women. As of now, 250 million peasants have been organized into the world’s largest non-secular social movement through the peasant federation of “La Via Campesina.” The peasant food web conserves much of the world’s biodiversity. Peasants also do this work with significantly less control and sovereignty over land than large private entities or state governments. Largely and unfortunately, this information is unknown to the general public in the so-called "united states."

VI.THE CASE FOR FOOD SOVEREIGNTY

With the total collapse of capitalism on our horizon, community-based food sovereignty can be pursued by the masses to sustain resistance movements, feed ourselves, and support autonomy.

Food sovereignty can be explained as a people’s ability to produce, distribute, and consume their own food in an ecologically sound way under their own terms and conditions, thereby meeting the nutritional needs of everyone involved in the process. In order for this to happen, people need access to land, water, and housing. Globally, the food sovereignty process takes place on a small scale with small holder farmers on two hectares or less.

However, the capitalist industrial food system scaled-up food production to never-before-seen levels through mechanization, paramilitary death squads that target and murder peasant organizers, chemical pesticides and fertilizers, land grabs, femicide, and exploitative labor practices used to massify profits. This has made food sovereignty unachievable for the masses of people in amerikkka to actualize. People are forced to thoughtlessly consume food sold in grocery stores drenched in toxic pesticides, or heavily processed food sold in corner stores packed with poisonous preservatives, leading to diet related diseases and premature death.

There is an overarching public blame on individuals for not switching to healthier diets, but consumption of industrialized food is designed to be highly addictive. Also access to arable land and healthy food is strategically inaccessible. In this context, food and food access becomes weaponized by corporations to enact physiological and psychological violence onto the masses. As explained, this is the current state of the colonial food system.

Currently, large numbers of domestic farmers are disposing of food because of the shutdown of so much of the economy. Not to mention, 30% of all food produced by industrial agriculture is already wasted. Meanwhile, food banks are experiencing unprecedented levels of strain as millions of people are furloughed. Farm laborers and food service workers have historically been regarded as disposable and unskilled, when in fact, this type of work is highly skilled and is being devalued to ensure the extraction of this labor is profitable. If food work and land tending are and always have been essential, why are peasants and workers in food economies so often actively exploited?

All this is to say that the organizational systems of labor and food production are almost totally ineffectual, wasteful and violently exploitative. The contemporary pandemic moment is bringing many of these dangerous gaps to light, but the colonial food landscape has been scamming and poisoning millions of frontline people for centuries. The frontline of these unsustainable systems creeps closer and closer to the consumer classes, and even on to the doorsteps of oligarchical capitalists. As these structures and food systems enter new frontiers of collapse, it will be the peasant way that catches our communities, it will be communal and reciprocal relationships with land that hold the possibility of justice and liberation.

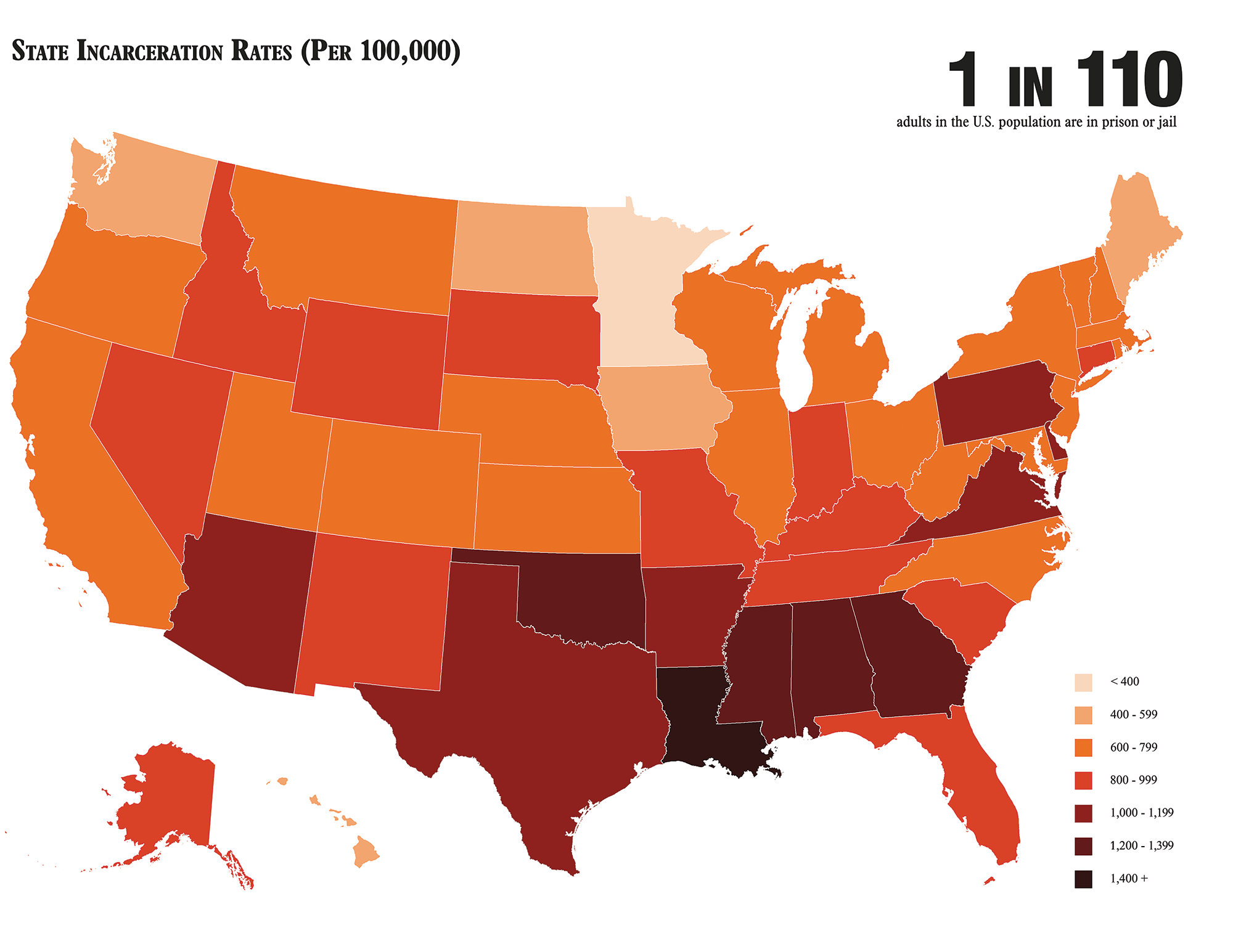

Infographics: U.S. Prison Statistics

tap to expand

Graphic Source: McKinney, Dana. “Societal Simulations A Carceral Geography of Restoration” Harvard Graduate School of Design. January 2017.

Data Source: Rabuy, Bernadette and Daniel Kopf. Prison Policy Initiative. “Separation by Bars and Miles: Visitation in State Prisons.” October 20, 2015.

by the homies, for the homies: a column

In A Pandemic, Prison Abolition Is Necessary And More Possible Than Ever

by Benji Hart (written April 22, 2020)

COVID-19 has upended life in the U.S. in ways no one could have predicted. Entire sectors of the workforce are jobless, thousands of families are struggling, to say nothing of the human toll, the collective anxiety and grief millions carry in quarantined isolation.

The pandemic has resulted in a global health crisis, exacerbating existing geographic, racial, and economic disparities. Yet, as governments and communities the world over scramble to combat the chaos, COVID-19 has also opened the door for radical political shifts that seemed impossible only weeks ago.

In Detroit, Michigan, water shutoffs were suspended—a measure to which residents are fighting to hold the city accountable; In Minnesota, grocery store employees, once considered “unskilled,” have been declared essential workers, and given free childcare to support them on the job; numerous states have temporarily halted evictions; despite schools being closed, many are still distributing thousands of free meals to families who need them; in California and Illinois, the state started offering vacant hotel rooms to those without housing; banks have paused payments on mortgages and student loans; and federal and local governments are giving out checks to cover food and rent costs.

Reading like a progressive manifesto, these measures are plucked directly from the platforms of grassroots campaigns for union power, housing, for racial and economic justice. They aren’t just happening because the crisis demands them, but because social movements have already laid out the template for a just society that COVID-19 has rendered more plausible.

Reading like a progressive manifesto, these measures are plucked directly from the platforms of grassroots campaigns for union power, housing, for racial and economic justice. They aren’t just happening because the crisis demands them, but because social movements have already laid out the template for a just society that COVID-19 has rendered more plausible.

These developments are worth celebrating, and not merely because they are kernels of hope amidst the constant news of illness, death, and the terrifying authoritarian measures that have also taken root under the pandemic. They are worth celebrating because they are a testament to the success of a host of progressive movements, specifically those for prison abolition.

From local campaigns to national policy, calls for divestment from the police and prison system were growing long before COVID-19. The communities launching these calls—often poor, working, Black, indigenous, and immigrant people—don’t merely cite the racist roots and violent history of these systems as justification for their abolition, but insist that what fundamentally ensures public safety is the investing of resources, not surveillance and incarceration.

In Chicago, a youth-led coalition named #NoCopAcademy sustained a battle from 2017 to 2019 fighting the construction of a $95 million police academy in the predominantly Black Garfield Park neighborhood. The coalition demanded those millions be put into free mental health programs, public schools, and the other community supports the city is constantly cutting from its budget.

When the Chicago Teachers Union went on strike in October of 2019, they continued these demands by using collective bargaining to advocate for affordable housing for their students, and a nurse at every school—measures city officials insisted were outside of the union’s jurisdiction. Though mayor Lori Lightfoot dismissed CTU’s negotiations as fiscally implausible, she found money to up the contract that keeps Chicago Police patrolling public school hallways from $22 to $33 million.

CTU vice president Stacey Davis Gates posed the question to parents at a press conference: “Do you want a police officer in your school, or do you want a restorative justice coordinator in your school that can provide your child with how to deal with conflict, not how to be penalized for conflict?”

The unprecedented demands of CTU seem prescient now that the city is scrambling to shelter those who are unstably housed, and expand health services to stop the spread of COVID-19. And as we learn together what it takes to protect our communities during a pandemic—and how we respond to their inevitable recurrence—we must also ask which models for community safety we will look to in the future.

There are countless struggles offering us those models right now. COVID-19 hasn’t merely pressured the state to take previously unimaginable actions, but inspired everyday people and grassroots movements to do the same: An eruption of mutual aid projects have reminded communities to look inward for collective support during moments of catastrophe: food waste is being redistributed to those in need; GE workers demanded their factories increase ventilator production to save jobs and lives; unstably housed families on the west coast have taken over state-owned homes; tenants around the country are calling for rent strikes and advocating for rent control; essential workers like bus drivers, janitors, and grocery store clerks are organizing for the wages and protections they’ve long been denied; and Amazon employees, whose CEO is the richest man on earth, are striking to demand paid leave and the sanitizing of their facilities to keep themselves and their families healthy.

On April 7th, several hundred drivers representing organizations from across Chicago descended on the Cook County Juvenile Center, ICE Headquarters, and Cook County Jail in a social distancing caravan to demand the mass release of all detainees—no matter the agency detaining them nor the charges they’re facing—in order to prevent the deadly spread of COVID-19 in prisons and jails. They insisted that public health means just that: the wellbeing and protection of those on both the inside and outside.

A pandemic cannot be contained in one quadrant while being allowed to thrive in another, just as decarceration is ineffective unless it is coupled with expanded access to housing and education, guaranteeing the necessary support for those exiting prisons. None of us are safe until all of us have access to the care we deserve.

It is disappointing that it has taken a pandemic for the powerful to even consider listening to the needs of those most targeted by the police and prison system. Yet, it is precisely those needs that point to both the most radical and the most reasonable solutions to COVID-19. And from universal healthcare to guaranteed minimum income, from decarceration to housing for all, who knows how these visions might live on after the pandemic, how many may forever reevaluate what they believe to be feasible.

Organizer Kelly Hayes said wisely in the wake of horrifying rallies held by white nationalists against their states’ stay-at-home orders, “The politically impossible is now possible, and that cuts both ways.” The shift towards a police and prison free world—towards the dramatic restructuring of every facet of resource distribution in our society—is not inevitable. It requires reinvigorated organizing, fierce advocacy, and a staunch commitment to resisting the gathering fascist forces that oppose it.

But in moments of profound upset like COVID-19—when the demands of the most marginalized are proving themselves to be the only hope for survival we have—it is more possible than ever.

VOICES OF DBI CAPTIVES:

Mission Statement

by Dawud Lee

#VoicesofDBICaptives is a bulletin designed to explain to the general public what DBI means. DBI literally means Death By Incarceration, or that the men, women, and children who are sentenced in such a draconian manner will ultimately die inside of a cage, euphemistically referred to as a cell. Therefore, those of us unfortunate enough to be serving such a sentence of slow death are calling upon the activist community, and other caring human beings to assist us as we work towards creating an open door that we can walk through, and once again experience life from the standpoint of the outside world. We understand that by telling part of our story we can shed light on our current situation, as well as speak to the political and economic realities of our incarceration.

A life sentence, or DBI sentence, means that those unceremoniously sentenced to DBI will literally spend the remainder of their lives inside a cage, and ultimately die inside that cage like incorrigible animals not deserving of any sort of human decency, mercy, or an opportunity to redeem themselves, and in cases where a person is innocent, just dying an unjust death! Yes, there is a legal process, but this process is mired in more draconian measures, and those measures are not designed to free folks coming from impoverished or powerless backgrounds, and this is not to even speak about the racism, which is prevalent throughout the American judicature. Therefore we’re forced to seek relief in other manners, and this brings us directly in the political arena as we seek out solutions to our existing problems associated with this agonizing degree of captivity. Ergo, we are humbly asking more folks to join those dedicated activists already engaged in this work on both sides of the barricade as we develop ways to offer opportunities for those with DBI sentences with a life beyond cages.

Here in our second issue of #VoicesofDBICaptives, we are going to speak largely about the traumas we have experienced in our lives, and how those traumas related to some of the poor decisions we made. We have been introduced to concepts like ACE’s, which means Adverse Childhood Experiences Study, and PTSS or Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome and we understand how the traumas in our lives play a major role in the dysfunctional behaviors taking places in our communities around the country. We also understand the importance of studying these issues as we search for realistic solutions to the problems that we are confronted with here in this country. ACE’s helps to explain why so many people from inner-city communities continue to make unhealthy decisions. Whether those unhealthy decisions lead to drug use, unhealthy eating, unhealthy relationships, vacant esteem, unsafe sexual intercourse, or some other unhealthy decisions, we need to evaluate what is taking place in our lives and find some honest solutions.

VOICES OF DBI CAPTIVES:

Understanding my Childhood Traumas

By Nyako Pippen

The year was 2006, I was 18 years old, and I felt as if the weight of the world was on my shoulders. I was out on bail for several different drug-related charges, and my then-girlfriend had recently given birth to our baby girl. I was unemployed, and was operating on a 5th grade educational level. On top of all that, it was looking like I would end up serving a two to four year sentence for the drug cases. To say that I was in a constant state of worry and anxiety would grossly under state my mental disposition at that time in my life.

The year was 2006, I was 18 years old, and I felt as if the weight of the world was on my shoulders. I was out on bail for several different drug-related charges, and my then-girlfriend had recently given birth to our baby girl. I was unemployed, and was operating on a 5th grade educational level. On top of all that, it was looking like I would end up serving a two to four year sentence for the drug cases. To say that I was in a constant state of worry and anxiety would grossly under state my mental disposition at that time in my life.

My younger sister Amina and I have always been very close. Amina is two years younger than I am, and throughout our entire lives she has always followed me around, paying close attention to my every move. Despite her being my younger sister Amina has constantly scolded me for hanging out with a certain crowd, or engaging in dangerous activities. It’s safe to say that she stayed on my case. Therefore, it was no surprise when she asked me the question, “what if something happens to you in those streets?” It was not the concern in her voice or demeanor that caught my attention, rather it was the fact that up until that point I had never considered the question of what if? Even with the birth of my child and the previous encounters with the law, my mindset was to “get rich or die trying,” and I was literally willing to die in my pursuit of money. Sadly, the answer to my little sister is enough to prove my mental state at that juncture in my life. I said to her, “if I could leave my family a million dollars, I don’t care about dying or spending the rest of my life in jail.”

Now that I am thirty-one years old and serving a DBI sentence, I often reflect back on that conversation with my sister, and I ask myself what went so wrong in my life that would cause me to develop such a hopeless outlook? What was it that placed me in such a desperate mental state? Through many years of survival inside of a cage, I continuously searched for some answers, and my best guess is that I was just trying to find myself. My search consisted of me reading a lot of religious material and self-help books, which emphasized the importance of me moving on and forgetting my past. Also, I engaged in many stimulating conversations with my father, and we sometimes revisit the past in an attempt to unravel some of the dysfunction that has plagued our family for many years. My studies and conversations ultimately led to a lot of mental and spiritual development. Notwithstanding, I still felt an enormous void in my life, and I still lacked a sense of purpose, which I believe that all human beings need to help us find direction in our lives. Going back to some of my religious and self-help studies, I agree with the notion of moving on, but we should not allow our past to define our future. However, if we want to properly heal from the years and years of traumas we have been exposed to, then it is imperative for us to understand the origins of our distorted thinking and behaviors.

After being introduced to the book Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome (PTSS), I began the process of really looking at the traumas in my life, and the traumas in the lives of my family, and in a larger sense, the traumas in our community and the country: Dr. Joy DeGruy eloquently explained the concept of Trans-Generational trauma, and she articulated how traumatic encounters can be passed down from generation to generation. Moreover, she expressed how the traumas associated with the deplorable institution of slavery affects us to this very day. In my continued search for answers, I was fortunate enough to be introduced to the ACE’s concept. ACE’s stands for Adverse Childhood Experience Study. The ACE study has proven that certain childhood exposures to trauma can cause medical problems, early death and other life-long ill effects if not properly addressed. Upon familiarizing myself with these concepts, I began to gain a broader understanding of how I fell into such a dejected, mental state.

All the early memories of my existence are filled with hardship and trauma. The house I spent the first six or seven years of my life in could have easily been mistaken for an abandoned house. There were unfinished hardwood floors, peeling paint, and leaking ceilings, which were all very visible. I can still recall the time that the wall dividing the kitchen and the backyard caved in, and my father simply replaced the wall with a piece of heavy duty plastic, which acted as a wall for numerous seasons, and this includes winter. On numerous occasions we went without basic utilities, mainly the electricity being off. I remember a time during thanksgiving when my five other siblings shared a meal that my mother prepared for us on a kerosene heater.

Aside from our extremely impoverished conditions, I also witnessed two physical altercations between my parents. However, they were not as harsh as the stories told to me by my siblings about how my father brutally abused my mother. Including how my father stabbed my mother in the chest and threw her down a flight of stairs. Ultimately, my mother decided to leave.

My mother moved us to a low income-housing complex located in Pottstown, Pennsylvania. Our new apartment was the nicest place I had ever seen in my life. Nice white walls, carpet throughout the apartment, and a central air conditioner. Despite all the luxuries we now had, I still cannot distinguish what years were worse in terms of my development. Although our living arrangements were far better than it had been in the past, I was introduced to another aspect of life that I was simply not ready to handle. I had my first taste of how poverty affected me socially. I attended a school that consisted of middle class blacks and whites, and I began to be teased due to my appearance. The teasing usually led to me getting into fights to defend my honor arid also getting suspended from school.

Social rejection was just one of the hardships we had to deal with during those years. By far the hardest thing my family was dealing with was my mother’s drug addition. I recall her staying out for nights and days at a time, and when she returned she would spend a lot of time in the bathroom and then fall asleep for hours and days at a time. She tried her hardest to keep her addiction away from us; however, it inevitably spilled over into our lives when the other kids in the neighborhood teased us about it. Also I remember having a summer job working for Dominoes where my older sister and I would pass out flyers for a few hours on the weekend. We would get paid $21.00 for the weekend. On many occasions my mother would ask to borrow our money. Of course we would oblige, never receiving the money back. Ultimately, her addiction led to our homelessness.

Throughout my journey to find healing and balance in my life, I began to question my parents parenting skills. However, as I became more informed, I had to take a look at their possible ACE levels. I remember my mother telling me about a time when she was younger and my uncle raped her, and when she revealed this to my family, they denied her accusation and eventually shunned her. Or when her father nearly beat her half to death, because she discarded his heroin, in an attempt to help him quit the deadly drug. Unfortunately, there came a time when she began to use with him.

Throughout my journey to find healing and balance in my life, I began to question my parents parenting skills. However, as I became more informed, I had to take a look at their possible ACE levels. I remember my mother telling me about a time when she was younger and my uncle raped her, and when she revealed this to my family, they denied her accusation and eventually shunned her. Or when her father nearly beat her half to death, because she discarded his heroin, in an attempt to help him quit the deadly drug. Unfortunately, there came a time when she began to use with him.

February 16, 2007 was the day I was arrested for the crime in which I am currently incarcerated. Coincidentally my arrest took place right there on the 200 block of E. Armat St. in the house my father still owns, the house that just 19 years prior to that unfortunate night, a much more profound arrest took place, a psychological arrest in the form of trauma. It is the ACE study and the PTSS concept that has allowed me to look at my family and my life as a whole, from a completely different perspective. I no longer view the bad times as just bad memories, as thoughts to be forgotten. I now understand that those events are far more than mere memories. Those events helped mold and shape my core beliefs and dictated my instincts. I understand that my insatiable desire for money derived from certain traumas that transpired throughout my life. Understanding the circumstances of my life, I began to develop a sense of purpose, which would provide the much needed wisdom to allow me to place ires in their proper places in my life.

David Lee #AS3041 and Nyako Pippen #6180 can be reached at:

Smart Communication/PA DOC

SCI Coal Township

PO Box 33028

St. Petersburg, Florida 33733

Both are members of CADBI (Coalition to Abolish Death By Incarceration) and are working to change legislation in the state of Pennsylvania.

For more information on CADBI:

Visit: Decarceratepa.info/CADBI

Call: (267) 606-0324

Email: CADBiphilly@gmail.com