BLACK HISTORY MONTH

Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4

An End To The Neglelct Of The Problems of The Negro Woman!

by Claudia JonesClick here

After The Take-Over

by Marielle FrancoThough the entire legal machinery was mobilized to justify it, the impeachment of Brazil’s first female president was an authoritarian act. On one side: the President, Dilma Rousseff, a woman seen by a significant section of the population as of the left. On the other: a man, white, understood by many as embodying the right, and an organic member of the dominant social class. In the aftermath of Dilma’s overthrow, the balance of forces in Brazil has been tilted in favour of the most conservative sections of the ruling class. This implies significant social changes in the sphere of state power and the public imagination, at a time when inequalities are widening, and the withdrawal of rights, the spread of discrimination and the criminalization of dispossessed young people and women—above all poor black women—is on the rise. The democratic process that opened up from 1985, with the end of the military dictatorship, is now being suffocated, initiating a new crisis that poses deep challenges for the left.

This essay sets out to analyse the social conditions of Brazilian women in the context of this conjuncture, bearing in mind, first, the wide variation in women’s positions in a city like Rio—in their cultural outlooks and worldviews, their daily lives and political activity, their socially grounded situations. Second, black women from the favelas face inequalities that distinguish them from women of other social strata—the middle class, and those who don’t work for a living. In this sense, beyond analysing the position of women in general, my central concern here is to identify that of women who suffer not only from the institutional machismo of Brazilian society, but also the impact of the structural racism that is hegemonic here. Third, I want to draw attention to the women working in the poorest and most precarious conditions. This goes for the majority of women in the favelas and other marginalized urban districts, who nevertheless remain a powerful force for creativity and inventiveness, with the capacity to overcome their circumstances through their daily struggles and forms of local organizing. It is through these multiple activities that women have taken on a central role in cities like Rio de Janeiro.

There are some conditions that are specific to the lives of women from the favelas, which should be taken into account in any consideration of the varying levels of social, economic and cultural inequality. Neighbourhoods lack government resources or infrastructure, with poor public transport, making it hard to access the areas where the major educational, work and cultural centres are concentrated, which in turn has an impact on the time that can be spent in study, leisure and family life. Second, class distinctions also operate in the favelas, even though all are workers; precarious labour conditions and contracts exert a range of different pressures. Exposure to lethal violence is a common condition, as is the experience of discrimination and stigma. Finally, it’s worth noting again the creativity of these women, motivated by the need to surmount their objective circumstances and claim alternative spaces for artistic, educational and political activity, as well as varied forms of subsistence work. Developing an analysis based on this complex objective situation, while also taking into account the subjective factors entailed in the ideological arguments, narratives and institutionalized power of dominant discourses, is a crucial exercise for understanding and intervention in the current conjuncture.

After this brief outline of the category ‘favelada woman’, we need to substantiate how these women live, feel and act on a daily basis, confronted with the effects of the recent right-wing ‘coup’. The emergency of life has always been a vivid reality for these women. They have always lived the consequences of the state’s crackdown on rights and the imposition of policies aiming at interdiction and domination. Periods of ‘social well-being’ in Brazilian history have been hard-won achievements, rather than concessions granted by those in power. Although institutional machismo has been one of the bases of Brazil’s social formation, black favelada women also encounter other forms of domination. But the present political situation, characterized by the hardening of state power and the pre-eminence of an authoritarian-conservative white male, intensifies this dynamic.

While the lived experience of these inequalities, running throughout Brazilian history, has a greater impact on the peripheries and the favelas, these women are not defined by impoverished passivity—contrary to their representations in mainstream discourse and the media. They have taken on central roles in the fight for state policies that challenge inequality and expand the human dimensions of civil rights. In this way, they have succeeded in making changes at a neighbourhood level that make powerful claims as new sites for the popular imagination and for social relations. In their engagement in everything from the arts to social and political practice in the marginalized districts, the presence of these women resonates through the city. It is worth emphasising that the peripheries and the favelas are part of the city—not separate from it. What distinguishes them from the other districts is the way the residents in these communities organize themselves, beyond the low public investment in their lives.

The life trajectories of these women—particularly black and mixed-race women, who make up the majority—are driven by an instinct for survival, for themselves and their families. They build networks of solidarity focused on sustaining lives and reinforcing dignity. While they bear the brunt of Brazil’s unequal social formation, they are also the ones who produce the means for transforming it, expanding mobility in every dimension. In this sense, they will be most sharply penalized in the current context, while at the same time they are centrally positioned to resist. The term ‘survival’ here goes beyond the maintenance of life—even in the face of the growing wave of femicides in Brazil (in 2015, two-thirds of the victims were black). Survival also involves housing conditions, food, health, clothing, schools, working lives, means of transport, access to culture; it goes beyond any purely economic definition to include the multiple dimensions of life. Today, these bodies in the peripheries are the principal site of exploitation and control imposed by the capitalist order—replacing the ‘industrial body’. In this context, black women from the peripheries, especially the favelas, can be key instantiations for democratic advance, co-existence with difference and overcoming inequality.

Although the cultural activism and political militancy of these women is initially related to local issues, and intimately linked to the objective and subjective conditions of their lives, the local advances they have won have an impact throughout the city. In this sense, there are numerous outstanding favelada women, whose actions and representations transcend the environment that predominates over their lives. This is not a matter of individuals being particularly enlightened or special, but a question of trajectories, encounters, perceptions of self and other, opportunities, and engagement with social issues. In a positive sense, this phenomenon, already on the rise before the right-wing takeover, poses the challenge to the left of how to sustain its momentum as a way of overcoming the conservative wave now sweeping across Brazil.

However, a considerable number of favelada women view political participation with some distrust. They are unlikely to be in touch with those who can access state institutions—seen by the majority as belonging to the undifferentiated ranks of the political elite. This segment has been growing, as the dominant classes succeed in spreading the idea that the most serious problem facing Brazil is not inequality, but corruption. The more this perspective takes hold of the collective imagination, the more people will reject political participation and identify ‘the politicians’ as the main cause of corruption. Measures benefiting the poor have rarely been a priority in Brazil. This in turn reinforces the prevailing mode of fear, of non-involvement with political decisions, which only serves to thicken the authoritarian atmosphere and lower the level of participation, including the vote (just look at the growth of blank votes and abstentions). Distrust of the ruling class has always existed—a sense that no change ever lasts, that everything is temporary and short-dated. With the right-wing takeover this feeling has strengthened its grip on the popular imagination, become an impediment to democratic advance that we must overcome.

Unemployment and precarious work have always predominated in the favelas, though solidarity has helped create the conditions for resistance. As well as the certainty that we can never stop, that life is a permanent struggle, this environment produces its own resources for going beyond these immediate surroundings and succeeding on a larger scale. Although the advances of recent years are now under severe threat, it would be wrong to say that nothing had changed, that everything remains as it has always been. Despite the realities of inadequate day-care centres and schools, poor job prospects, little access to the arts, language studies or the resources of human history, these urban peripheries recognizably produce multiple forms of intelligence—and women occupy a strategic place in this process. The task of the left in the twenty-first century is to expand this potential, creating narratives that foreground the freedom, participation and emancipatory activism of black favelada women.

The uncertainty hanging over the Bolsa Família welfare programme already foreshadows a return of the needy to the doorsteps of the church. Intensified by the right-wing takeover, the feeling of a lack of horizons, an absence of perspective, feeds the sense of pessimism, the refusal to think beyond tomorrow. In these conditions, it’s all the more important for the left to register the achievements of black and favelada women and their transformative potential. Contesting ways of seeing, feeling and thinking in a world of constant change, situating black women’s deeds—as they fight to overcome the impacts of institutional racism—in these contested spaces: this is the challenge.

Running counter to the apathy and cynicism, other elements are pulsating through Rio de Janeiro, distinct from those that predominate at the national level. The historic election, with 46,000 votes, of a black favelada feminist councillor, on the political left, stands in contradiction to the logic of Temer’s takeover. This suggests the importance of occupying the spaces of state power, especially the institutions, by way of participating in elections and contesting authoritarian meritocracy to break up, as much as possible, the white male contingent that dominates these environments. The stereotypes associated with being a woman, and the expectations for how we should behave, are facets of a hegemonic institutional discourse that remains deeply conservative. This reactionary movement is only gaining momentum, as the outcomes in the us and uk suggest. At the international level, wars and persecution manifest themselves as forms of control, each one worse than the last, imposed upon the excluded body of ‘the other’. The misleading narrative of the ‘economic crisis’ is used as a cover for the roll-back of rights, leaving those in the favelas, especially poor black women, even more vulnerable to the violence and institutional racism that are deep in the social pores of Brazil.

Temer’s illegitimate, authoritarian and conservative government expands the stranglehold of the political and economic elites who dominate Brazil. That is why police repression has intensified in the face of popular protests, along with the war-on-drugs discourse that strikes at the heart of the peripheral zones. The counter-reforms on labour and social security are further examples of the attack on rights, affecting women in particular, especially those who live by their labour or rely on the work of their families for survival. This marks the experience for black favelada women on a national scale. In this conjuncture, which favours Bonapartism or the growth of conservative authoritarianism, the first response must be to move ahead with immediate, hard-hitting actions, building support for campaigns that emerge out of the moment, such as ‘Direct Elections Now’—recalling the Diretas Já movement of the early 1980s—or ‘Not One Right Less’. Second, defending lives against lethal violence and fighting for human dignity. Third, developing policies that undermine capital’s strategies in Brazil. Fourth, strengthening the narrative of full coexistence in cities like Rio, to sway the public imagination towards the crucial challenge of overcoming inequalities. Finally, to centre as social actors those from the margins and the favelas throughout Brazil. Building structures that help empower poor, black women to take on the role of active citizenship, aimed at winning a city of rights, is fundamental for the revolution the contemporary world requires.

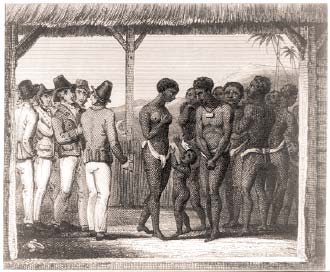

A Journey Along the Atlantic Slave Route

by Saidiya Hartman1. The Path of Strangers

I HAD COME TO GHANA in search of strangers. The first time for a few weeks in the summer of 1996 as a tourist interested in the slave forts hunkered along the coast and the second time for a year beginning in the fall of 1997 as a Fulbright Scholar affiliated with the National Museum of Ghana. Ghana was as likely a place as any to begin my journey, because I wasn’t seeking the ancestral village but the barracoon. As both a professor conducting research on slavery and a descendant of the enslaved, I was desperate to reclaim the dead, that is, to reckon with the lives undone and obliterated in the making of human commodities.

Saidya Hartman for Narrative, 2007

Saidya Hartman for Narrative, 2007

I wanted to engage the past, knowing that its perils and dangers still threatened and that even now lives hung in the balance. Slavery had established a measure of man and a ranking of life and worth that has yet to be undone. If slavery persists as an issue in the political life of black America, it is not because of an antiquarian obsession with bygone days or the burden of a too-long memory, but because black lives are still imperiled and devalued by a racial calculus and a political arithmetic that were entrenched centuries ago. This is the afterlife of slavery—skewed life chances, limited access to health and education, premature death, incarceration, and impoverishment. I, too, am the afterlife of slavery.

Nine slave routes traversed Ghana. In following the trail of captives from the hinterland to the Atlantic coast, I intended to retrace the process by which lives were destroyed and slaves born. I stepped into the path of more than seven hundred thousand captives, passing through the coastal merchant societies that acted as middlemen and brokers in the slave trade, the inland warrior aristocracies that captured people and supplied slaves to the coast, and the northern societies that were raided and plundered. I visited the European forts and storehouses on the three-hundred-mile stretch of the littoral from Beyin to Keta, the slave markets established by strong inland states that raided their enemies and subordinates and profited from the trade, and the fortified towns and pillaged communities of the hinterland that provided the steady flow of captives.

I chose Ghana because it possessed more dungeons, prisons, and slave pens than any other country in West Africa—tight dark cells buried underground, barred cavernous cells, narrow cylindrical cells, dank cells, makeshift cells. In the rush for gold and slaves that began at the end of the fifteenth century, the Portuguese, English, Dutch, French, Danes, Swedes, and Brandenburgers (Germans) built fifty permanent outposts, forts, and castles designed to ensure their place in the Africa trade. In these dungeons, storerooms, and holding cells, slaves were imprisoned until transported across the Atlantic.

Neither blood nor belonging accounted for my presence in Ghana, only the path of strangers impelled toward the sea. There were no survivors of my lineage or far-flung relatives of whom I had come in search, no places and people before slavery that I could trace. My family trail disappeared in the second decade of the nineteenth century.

Unlike Alex Haley, who claimed the sprawling clans of Juffure as his own, grafted his family into the community’s genealogy, and was feted as the lost son returned, I traveled to Ghana in search of the expendable and the defeated. I had not come to marvel at the wonders of African civilization or to be made proud by the royal court of Asante, or to admire the great states that harvested captives and sold them as slaves.(i) I was not wistful for aristocratic origins. Instead I would seek the commoners, the unwilling and coerced migrants who created a new culture in the hostile world of the Americas and who fashioned themselves again, making possibility out of dispossession.

By the time the captives arrived on the coast, often after trekking hundreds of miles, passed through the hands of African and European traders, and boarded the slaver, they were strangers. In Ghana, it is said that a stranger is like water running over the ground after a rainstorm: it soon dries up and leaves behind no traces.(ii) When the children of Elmina christened me a stranger, they called me by my ancestors’ name.

Stranger is the X that stands in for a proper name. It is the placeholder for the missing, the mark of the passage, the scar between native and citizen.(iii) It is both an end and a beginning. It announces the disappearance of the known world and the antipathy of the new one. And the longing and the loss redolent in the label were as much my inheritance as they were that of the enslaved.

Unwilling to accept the pain of this, I had tried to undo the past and reinvent myself. In a gesture of self-making intended to obliterate my parents’ hold upon me and immolate the daughter they hoped for rather than the one I was, I changed my name. I abandoned Valarie. She was the princess my mother wanted me to be, all silk and taffeta and sugar and spice. She was the pampered girl my mother would have been had she grown up in her father’s house. Valarie wasn’t a family name but one she had chosen for me to assuage the shame of being Dr. Dinkins’s outside daughter. Valarie was a name weighted with the yearning for cotillions and store-bought dresses and summers at the lake. It was a gilded name, all golden on the outside, all rawness and rage on the inside. It erased the poor black girl my mother was ashamed to be.

So in my sophomore year in college, I adopted the name Saidiya. I asserted my African heritage to free myself from my mother’s grand designs. Saidiya liberated me from parental disapproval and pruned the bourgeois branches of my genealogy. It didn’t matter that I had been rejected first. My name established my solidarity with the people, extirpated all evidence of upstanding Negroes and their striving bastard heirs, and confirmed my place in the company of poor black girls—Tamikas, Roqueshas, and Shanequas. Most of all, it dashed my mother’s hopes. I had found it in an African names book; it means “helper.”

At the time, I didn’t realize that my attempt to rewrite the past would be as thwarted as was my mother’s. Saidiya was also a fiction of someone I would never be—a girl unsullied by the stain of slavery and inherited disappointment. Nor did I know then that Swahili was a language steeped in mercantilism and slave trading and disseminated through commercial relations among Arab, African, and Portuguese merchants. The ugly history of elites and commoners and masters and slaves I had tried to expunge with the adoption of an authentic name was thus unwittingly enshrined.

I realized too late that the breach of the Atlantic could not be remedied by a name and that the routes traveled by strangers were as close to a mother country as I would come. Images of kin trampled underfoot and lost along the way, abandoned dwellings repossessed by the earth, and towns vanished from sight and banished from memory were all that I could ever hope to claim. And I set out on the slave route, which was both an existent territory with objective coordinates and the figurative realm of an imagined past, determined to do exactly this.

It was my great-grandfather Moses, my mother’s grandfather, who initiated me on this journey. On a hazy summer morning my brother and I set out with Poppa to learn about our people. The summer of 1974 would be the last time we visited Montgomery, Alabama, for anything other than a brief four-day trip, and Poppa, sensing this, introduced us to our past. Peter and I had outgrown the boundaries of Underwood Street and tired of the local kids who, in turn, had grown weary of us and too many sentences beginning “In New York,” which lorded the wonders of our world over the restrictions of theirs—really good Chinese food, the roller coaster at Coney Island, knishes, fire hydrants like geysers crashing on sweltering asphalt streets, and the one-hour mass where we were allowed to wear jeans and Sister Madonna played the guitar, instead of the all-day trial of Morning Pilgrim Baptist Church, where you were pinched if you nodded off and had to wear dresses and tights and jackets and ties, no matter how hot it was.

Poppa took us on a tour of the rural outskirts of Montgomery County, where our people had lived before moving into town. As we drove through the monochromatic brown stretch of farmland broken only by dull grazing cows, Poppa would stick his hand out the window at regular intervals and declare, “Land used to be owned by black folks.” Now agribusiness owned everything as far as the eye could see.

Looking at all the land worked by us but that was no longer ours triggered Poppa’s memory. No doubt he remembered his grandfather, whose land had been stolen by a white neighbor upon his death, forcing his wife and children off the property. White neighbors had poisoned his well and killed his farm animals, trying to drive him off the land, but only after his death did they succeed in evicting his family and taking his property with a fraudulent deed. In the middle of explaining how black farmers lost it all—to night riders, banks, and the government—Poppa drifted into a story about slavery, because for men like Poppa and my great-great-great grandfather to be landless was to be a slave. He called slavery times the dark days.

What I knew about slavery up until that afternoon with Poppa had been pretty basic. Of course I knew black people had been enslaved and that I was descended from slaves, but slavery was vague and faraway to me, like the embarrassing incidents adults loved to share with you about some incredulous thing you had done as a toddler but of which you had no memory. It wasn’t that you suspected them of making it up as much as it concerned some earlier incarnation of yourself that was not really you. Slavery felt like that too, something that was part of me but not me at the same time. It had never been concrete before, not something as palpable as my great-grandfather in his starched cotton shirt sitting next to me in a brown Ford, or a parched red clay country road, or a horse trader from Tennessee, or the name of a girl, not much younger than me, who had been chattel.

Slavery was never mentioned at my school, Queen of All Saints, although I learned about Little Black Sambo from my fourth-grade teacher, Mrs. Conroy, whose lilting Irish tones mollified offense. When I wore Afro puffs, she called me an African princess, provoking the derisive laughter of my classmates, black and white alike. Nor was slavery discussed at the Black Power summer camp where, unbeknownst to my parents, who recognized only that the camp was free and in walking distance from our house, counselors forbade us to apologize to white people, where I wore T-shirts embossed with revolutionary Swahili slogans, the meanings of which I could never remember. The counselors taught us to disdain property, perform the Black Power handshake, and march in strict formation, but they never mentioned the Middle Passage or chattel persons.

As we drove through the countryside, Poppa told us his mother and grandmother had been slaves. His grandmother Ellen was born in Tennessee around 1820. She was a nursemaid for a horse and mule trader. As a house slave, she was spared the onerous work of the field, dressed better than the hands, dined on crumbs and leftovers, and traveled with her owners. Yet the relative advantage she might have enjoyed when compared with other slaves didn’t prevent her from being sold when her owner discovered himself in a “situation.”

Ellen had accompanied her master and his family on a trip to Alabama, where he went to sell a parcel of horses. Something went wrong in Alabama and she was sold, along with the horses. Maybe an unlucky hand at cards or outstanding debts or quick cash were what went wrong, at least for Ellen. In Tennessee, she might have had children of her own because nursemaids were often wet nurses who suckled their master’s children. If she was lucky her mother might have lived with the family too. If she had children or a mother or a man back in Tennessee, then she was separated from them without a good-bye.

Poppa’s mother, Ella, was born in Alabama and still a girl when slavery ended. He said less about her than about his grandmother, maybe because his grandmother raised him or maybe because speaking of his mother made him feel like the grief-stricken fifteen-year-old he had been in 1907 when she died. He preferred to stick to the essential facts—birth, death, and emancipation.

Sometime in 1865, a Union soldier approached Ella in the middle of her chores. “A soldier rode up to my ma and told her she was free.” The starkness of Ella’s story stunned me. Her life consisted of two essential facts—slavery and freedom juxtaposed to mark the beginning and end of the chronicle. But this was what slavery did; it stripped your history to bare facts and precious details.

I don’t know if it was the bare bones of Ella’s story or the hopefulness and despair that lurked in Poppa’s words as he recounted it, as if he were weighing the promise of freedom against the vast stretches of stolen land before him, that made me eager to know more than what Poppa remembered or wanted to share. Peter and I listened, silent. We didn’t know what to say.

Poppa didn’t remember any kin before his grandmother, who smoked a corncob pipe. He had inherited his love of pipes from her. It was one of the things I adored about him. He always smelled sweet like the maple tobacco smoke rising from his pipe. What he knew about our family ended with his grandmother Ellen. He remembered no other names. When he spoke of these things, I saw how the sadness and anger of not knowing his people distorted the soft lines of Poppa’s face. It surprised me; he had always seemed invincible, strapping, six foot two, and handsome, even at eighty-five. I had seen this ache in others too. At a barbecue at my grandmother’s, two of her cousins nearly came to blows disputing a grandfather’s name. I was still too young then to recognize the same feelings inside me. But I wondered about my great-great-great-grandmother’s mother, as well as all the others who had been forgotten.

If Poppa’s mother or grandmother shared any details about their lives in slavery, he didn’t share them with my brother and me. No doubt he was unwilling to disclose what he considered unspeakable. Still, he shared more with my brother and me than he had with my mother. Even now, he liked to call her “little girl.” When I returned home and asked her if Poppa had ever spoken to her about slavery or her great-grandmother Ella, the girl on the road, she replied, “When I was growing up we didn’t talk of such things.” Her great-grandmother had died before she was born, so my mother recalled nothing about her, not even her name.

At twelve I became obsessed with the maternal great-great-grandmother I had never known, endlessly constructing and rearranging the scene: her unease as the soldier advanced toward her, or the soldier on horseback looming over her and the smile inching across her face as she digested his words, or the peal of laughter trailing behind her as she turned upon her heels, or the war between disbelief and wonder that overcame Ella as she bolted toward her mother. Mulling over the details Poppa had shared with me, I tried to fill in the blank spaces of the story, but I never succeeded. Since that afternoon with my great-grandfather, I had been looking for relatives whose only proof of existence was fragments of stories and names that repeated themselves across generations.

Unlike friends who possessed a great trove of family photographs, I had no idea what my great-great-grandmother looked like or even my great aunts when they were girls. All these things were gone; some of the photographs were given as tokens to dead relatives and buried with them; others were lost. The images I possessed of them were drawn from memory and imagination. My aunt Mosella, whose name was itself a memorial to my great-grandfather Moses and his mother Ella, once described a photograph taken of her mother and my great-great-grandmother Polly, whom everyone called Big Momma. In the photograph, her mother, Lou, was wearing a ruffled dress with bloomers and seated on Big Momma’s lap. She didn’t remember what my great-great-grandmother wore but only re-echoed my mother’s description of her: she was a big-boned woman with a round face the color of dark chocolate.

Big Momma had never spoken of her life in slavery, nor had Ellen or Ella. Poppa could fill in only the bare outlines of their lives. The gaps and silences of my family were not unusual: slavery made the past a mystery, unknown and unspeakable.

The tales of the past that my mother had been willing to share were all about Jim Crow. She had grown up in a segregated world where essentially she was barred from childhood from parks and swimming pools and malt shops. Her reminiscences were replete with proscriptions; the simplest needs, whether for a drink of water or to use the bathroom, were regulated by the color line.

My father’s stories about racism were few. He remembered being called “nigger” for the first time as an enlisted man in the Air Force in Alabama, and he barely escaped being court-martialed after striking a white corporal. But I never heard him utter the words “slave” or “slavery.” I knew even less about my paternal kin. My father and his family did not hanker after unnamed ancestors or wonder what might have been. Their losses were too immediate. My grandparents had left Curaçao, a thirty-five-mile stretch of arid land adrift in the Caribbean Sea, vowing to make good in New York and to return home. But as the decades passed, they convinced themselves that it was still too soon, or that the money wasn’t right yet, or that it would be easier to leave the following year.

Not ready to admit the defeat of their permanent estrangement, they held steadfast to the belief in American opportunity. It was a word they uttered to stave off fear; it consoled them on bad days; it reminded them why they were in the States rather than at home. Opportunity—it was intoned as if it was the consolation they required, as if it repelled prejudice, warded off failure, remedied isolation, and quieted the ache of yearning. It shrouded the past and set their gaze solely on the future. The money sent home didn’t assuage the anger of mothers nursing abandonment or teenage children anticipating a life in the States they would never have. Nostalgia or regret could kill you in a place like America, so they banked only on tomorrow.

At the same time, they blamed America for everything that went wrong. America was the benediction and the curse. It was weather so frigid it brought you to tears. It was the high price of coal. It was your son’s insolence. It was your daughter’s refusal to speak Papiamento. America was the cause of every complaint and the excuse for every foul deed.

When it became clear that they would never return home, my grandparents erected a wall of half-truths and silence between themselves and the past. They parceled time, lopping off the past as if it were an extra appendage, as if they could dispose of the feelings connecting them to the world before this one and banish the dreams they had always imagined as the route back. In time, they decided the present was all they could bear. They died in the States with their green cards as the only proof that they had once belonged elsewhere.

Unlike my grandparents, I thought the past was a country to which I could return. I refused the lesson of their lives, which in my arrogance I had misunderstood as defeat. I believed that I would succeed in accomplishing what my grandparents had not; to me this meant tumbling the barricade between then and now, liberating my grandmother and grandfather from the small, small world of Park Place, and revisiting a history that began long before Brooklyn. So I embarked on my journey, no doubt as blindly as they had on theirs, and in search of people who left behind no traces.

I happened upon my maternal great-great-grandmother in a volume of slave testimony from Alabama, while doing research for my dissertation. I felt joyous at having discovered her in the dusty tiers of the Yale library. (Not Ella the girl on the road, but my great-grandmother Minnie’s mother, Polly.) When asked what she remembered about slavery, she replied, “Not a thing.” I was crushed. I knew this wasn’t true. I recognized that a host of good reasons explained my great-great-grandmother’s reluctance to talk about slavery with a white interviewer in Dixie in the age of Jim Crow. But her silence stirred my own questions about memory and slavery: What is it we choose to remember about the past and what it is we will ourselves to forget? Did my great-great-grandmother believe that forgetting provided the possibility of a new life? Was nothing to be gained by focusing on the past? Were the words she refused to share what I should remember? Was the experience of slavery best represented by all the stories I would never know? Were gaps and silences and empty rooms the substance of my history? If ruin was my sole inheritance and the only certainty the impossibility of recovering the stories of the enslaved, did this make my history tantamount to mourning? Or worse, was it a melancholia I would never be able to overcome?

“I do not know my father.” “I have lost my mother.” “My children are scattered in every direction.” These were common refrains in the testimony. As important were the silences and evasions, matters cryptically encoded as the “worst things yet” or the “dark days,” which exceeded the routine violence of slavery—whippings, humiliation, and separation from kin—and identified abuses that were beyond description: excremental punishments, sexual violation, and tortures rivaling anything the Marquis de Sade had imagined. Alongside the terrible things one had survived was also the shame of having survived it. Remembering warred with the will to forget.

My graduate training hadn’t prepared me to tell the stories of those who had left no record of their lives and whose biography consisted of the terrible things said about them or done to them.(iv) I was determined to fill in the blank spaces of the historical record and to represent the lives of those deemed unworthy of remembering, but how does one write a story about an encounter with nothing?

Years later when looking through the Alabama testimony, I was unable to find her. There was an Ella Thomas in the volume. Had I confused one great-great-grandmother with another? I reviewed my preliminary notes, desperately searched for the interview I had never copied, scoured five volumes, the two from Alabama and the adjacent ones, but there was no Minnie or Polly or anyone with a name similar, nor did I find the paragraph stamped in my memory: the words filling less than half the page, the address on Clark Street, the remarks about her appearance, all of which were typed by a machine in need of a new ribbon. It was as if I had conjured her up. Was my hunger for the past so great that I was now encountering ghosts? Had my need for an entrance into history played tricks on me, mocked my scholarly diligence, and exposed me as a girl blinded by mother loss?

The few traces of my great-great-grandmother had disappeared right before my eyes. This incident turned out to be representative. It served as my introduction to the slipperiness and elusiveness of slavery’s archive.

The archive contained what you would expect: the manifests of slavers; ledger books of trade goods; inventories of foodstuffs; bills of sale; itemized lists of bodies alive, infirm, and dead; captains’ logs; planters’ diaries. The account of commercial transactions was as near as I came to the enslaved. In reading the annual reports of trading companies and the letters that traveled from London and Amsterdam to the trade outposts on the West African coast, I searched for the traces of the destroyed. In every line item, I saw a grave. Commodities, cargo, and things don’t lend themselves to representation, at least not easily. The archive dictates what can be said about the past and the kinds of stories that can be told about the persons cataloged, embalmed, and sealed away in box files and folios. To read the archive is to enter a mortuary; it permits one final viewing and allows for a last glimpse of persons about to disappear into the slave hold.

I arrived in Ghana intent upon finding the remnants of those who had vanished. It’s hard to explain what propels a quixotic mission, or why you miss people you don’t even know, or why skepticism doesn’t lessen longing. The simplest answer is that I wanted to bring the past closer. I wanted to understand how the ordeal of slavery began. I wanted to comprehend how a boy came to be worth three yards of cotton cloth and a bottle of rum or a woman equivalent to a basketful of cowries. I wanted to cross the boundary that separated kin from stranger. I wanted to tell the story of the commoners—the people made the fodder of the slave trade and pushed into remote and desolate regions to escape captivity.

If I had hoped to skirt the sense of being a stranger in the world by coming to Ghana, then disappointment awaited me. And I had suspected as much before I arrived. Being a stranger concerns not only matters of familiarity, belonging, and exclusion but as well involves a particular relation to the past. If the past is another country, then I am its citizen. I am the relic of an experience most preferred not to remember, as if the sheer will to forget could settle or decide the matter of history. I am a reminder that twelve million crossed the Atlantic Ocean and the past is not yet over. I am the progeny of the captives. I am the vestige of the dead. And history is how the secular world attends to the dead.

2. The Family Romance

The white men who owned and sired the family line were phantasmal, as if we had conjured them up, and they threatened to vanish under the pressure of scrutiny. We uttered their names reluctantly, never forgetting that their names were also our names, but as if still fearing the punishment of thirty-nine lashes or the auction block for disclosing the identity of the father.

Every now and then my aunt Laura would share a story about “a German from Bonaire” or one of our other shadowy progenitors. Unlike my aunt Beatrice, who believed it was best to leave the past in the past and who was tight-lipped, especially when it concerned matters like indifferent fathers, troublesome origins, or other revelations that could only leave you shamefaced, my aunt Laura was willing to tell all. She relished the perverse details, liberating the skeletons from the closet and dutifully recounting the scandals that comprised our family history. Nothing fazed her, so whenever I wanted to find out some piece of information about the family that others considered taboo, she was the one to whom I turned.

Aunt Laura never shared any anecdotes about the ones who crossed the Atlantic from Africa. There were no anecdotes. “Genealogical trees don’t flourish among slaves,” as Frederick Douglass remarked. In my family, too, the past was a mystery. The story boiled down to remote white men, missing black fathers, lies and secrets about paternity, and wayward lines of descent. From time to time, my aunt Laura shared a name, Wilhelm Hartman or Rainer Hermann, or an attribute, “Hermann was a stingy SOB. That was all Mama ever said about him.”

Our genealogy added up to little more than a random assortment of details about alcoholics, prosperous merchants, and dispassionate benefactors. Given this paucity of information, all talk of our forebears was sketchy. No matter how much we embellished and dressed things up, the truth couldn’t be avoided: slaves did not possess lineages. The “rope of captivity” tethered you to an owner rather than a father and made you offspring rather than an heir.(v)

The classic story of slavery: A gray-haired gentleman succumbs to the evil of the peculiar institution and a wretched dark woman “lays herself low to his lust.” Who fails to recognize the figures, the planter and the concubine, the other tragic couple of the New World romance, a romance not of exalted fathers but of defiling ones? Who hasn’t heard it all before? The story of murky adulterated bloodlines, rapacious masters, derelict fathers, and violated mothers.

Bastaard was what the Dutch called their mixed-race brood; the term implied an illegitimate child as well as a mongrel. If these dead white fathers could speak, no doubt they would be hard-pressed to allow “son” or “daughter” to pass through their lips. Yet these ghostly patriarchs commanded more attention than anyone else in our battered line, if only because they could be named.

I had read numerous books and articles about the Dutch slave trade. I knew that the Dutch were the fourth largest slave-trading nation, falling in behind England, Portugal (in combination with Brazil), and France, and that from 1700 until the official end of the slave trade, the Gold Coast was a primary source of slaves for the Dutch.(vi) I knew that the Dutch called the female slave hold the hoeregat, or whore hold. I knew that Dutch ships were regular freight ships that had been refitted for slaves. I knew that slaves were forced to dance on deck to the accompaniment of African drums, flutes, and whips. I knew that of the 477,782 captives exported by the Dutch from 1630 to 1794, 89,000 were from the Gold Coast. I knew that this number might be an underestimation, but even if I multiplied it by ten or one hundred, all the missing and the dead still would not be of enough significance for the world to care or to acknowledge the crime. I knew that textiles, most of which were manufactured in Haarlem and Leiden, made up 57 percent of the goods the Dutch exchanged with African brokers for captives, and that guns, gunpowder, alcohol, and trinkets made up the rest of the merchandise traded. I knew that anywhere from 3 percent to 15 percent of the slaves held in the storerooms of Elmina Castle died there. I knew that slaves sometimes languished for as long as four months on board a slaver until a “complete cargo” had been purchased and that the journey across the Atlantic could take anywhere from 23 to 284 days. I knew that the slaves were called kop, or head, as in head of cattle, and not hoof ’d, as in human head. I knew a consignment of slaves was called armazoen, which meant living cargo, as distinct from other kinds of goods, and that the Dutch used the term “Negro” as an equivalent to “slave,” so they called the slave ship a neger schip, or Negro ship. I knew that the death rates of the slave trade, according to one Dutch historian, “reached 70% before the survivors were adjusted to life in the Western Hemisphere.”

But what did all this information add up to? None of it would ever compensate for all the other things that I would never know. None of it had brought me any closer to replacing a lacuna with a name or an X-ed space with an ancestral village.

For tracking purposes, the officials of the Dutch West India Company branded slaves twice. When captives arrived at Elmina Castle, Arabic numerals and/or the letters of the alphabet were seared onto their breasts. When they arrived in Curaçao, which was the way station for the slaves sold by the Dutch West India Company to the Spanish Americas,(vii) they were again branded with a red-hot iron. The scars identified the slaves at sales, at criminal proceedings, and in death affidavits,(viii) without which company officials were unable to say little more than, “It is the honest truth that on the first of March this year a certain purchased woman slave died, giving as the evidence of our knowledge that we saw the body after she died.”

The numbers identified each person as the cargo of a particular ship, or designated the company that purchased him, or simply itemized her as one unit, a pieza de India, or leverbaar.(ix) Slave ship officers traveled with instructions for branding: “Note the following when you do the branding: (1) the area of marking must first be rubbed with candle wax or oil; (2) the marker should only be as hot as when applied to paper, the paper gets red. When these [precautions] are observed, the slaves will not suffer bad effects from the branding.”(x)

A vivid picture of the purchase and branding of property was drawn by William Bosman, one of the chief factors at Elmina Castle. The scene he described was repeated at every port of embarkation along the West African coast. When a parcel of slaves arrived, the traders, accompanied by a surgeon, inspected them “without the least distinction or modesty.” The surgeon examined their eyes, prodded their teeth and genitals, and separated the healthy from the infirm. The ones deemed suitable, reported Bosman, “are numbered, and it is entered who delivered them. In the meanwhile, a burning Iron, with the arms or names of the companies, lyes in the Fire; with which ours are marked on the breast. This is done that we may distinguish them from the slaves of the English, French, or others (which are also marked with their mark); and to prevent the Negroes exchanging them for worse. I doubt not but this Trade seems very barbarous to you, but since it is followed by mere necessity it must go on; but we take all possible care that they are not burned too hard, especially the women, who are more tender than the men.”(xi)

WICS25 or T99—no one wants to identify her kin by the cipher of slave-trading companies, or by the brand, which supplanted identity and left only a scar in its place. I’m reminded of the scene in Beloved in which Sethe’s mother points to her mark, the circle and cross burned on her rib, and says to her daughter, “This is your ma’am. . . . If something happens to me and you can’t tell me by my face, you can know me by this mark.” The mark of property provides the emblem of kinship in the wake of defacement. It acquires the character of a personal trait, as though it were a birthmark.

Partus Sequitur Ventrem—the child follows in the condition of the mother. The bill of sale includes “future increase,” so that even the unborn were fettered. “Mothers could only weep and mourn over their children,” according to the ex-slave Mary Prince, “they could not save them.” The stamp of the commodity haunts the maternal line and is transferred from one generation to the next.(xii) The daughter, Sethe, will carry the burden of her mother’s dispossession and inherit her dishonored condition, and she will have her own mark soon enough, as will her daughter Beloved.

The mother’s mark, not the father’s name, determined your fate. No amount of talk about fathers could suture the wound of kinship or skirt the brute facts. The patronymic was an empty category, a “blank parody,”(xiii) a fiction that masters could be fathers and wayward lovers more than the “begetters of children”; it was as well the placeholder of banished black fathers.

My grandmother had been a Van Eiker, as had her mother and her mother before her. I was a descendant of a long line of fearless and strong-willed women—Leonora Van Eiker, Maria Julia Van Eiker, Elisabeth Juliana Van Eiker—who were denied marriage or eschewed it. Four generations were born with a blank space where a father’s name should be. In its place was the stroke of a bureaucrat’s pen, which had left a line less dramatic than an X and which suggested nothing as harsh as erasure but simply “not applicable.” My aunts Laura and Beatrice were proud to be Van Eikers; the other path, the dishonor that was the bastard’s inheritance as well as the slave’s, was too dangerous. The lessons they imparted tried to affirm this maternal inheritance and to make of it something other than monstrosity. The stories my aunts shared were offered as an antidote to shame and they esteemed a web of intimacy and filiation outside the law of paternal sanction.

I was a Hartman too. The predecessors of my grandfather Frederick Leopoldo were spectral figures. All I knew about my great-grandfather was that he had been a prosperous Jewish merchant. My aunts called him “Daddy’s father,” tacitly acknowledging that this blood relation did not extend beyond father and son and did not include them within its embrace.

The Hartman name, according to my father, was our anchor in the world. It was our sole inheritance; we possessed no wealth but it. So when my grandfather’s white cousins tried to buy back the family name from the brown ones in an attempt to erase a history of owners and property they feared would be mistaken for kinship, our clan doggedly held on to it. It had been passed from Wilhelm to Frederick to three generations of sons who were all named Virgilio.

Tracing the family geneology at the archives in Willemstad, the capital of Curaçao, I was surprised to discover that my grandfather wasn’t a Hartman at all.

On his birth certificate was the name Maduro, the surname of his mother, Clarita. I don’t know if his father had acknowledged him belatedly or if he had ever given his son permission to use his name as my aunt Laura insisted, or if Hartman was something my grandfather had pilfered as a man-child when at seventeen he set out into the world. Hartman was the name on his passport and his green card, and no doubt it would have been the name on my grandparents’ marriage certificate, if I had ever been able to locate it.

Growing up, I had envied my brother, who as son was the rightful heir to the Hartman name and who in turn would pass it on to his children. My father and mother had placed so much stock in the family name that even after getting married, I held on to it. But, as it turned out, there was no long lineage to which the name had been anchored or to which we had any entitlement. Who, after all, was the Hartman to whom we were

staking claim?

The Work You Do, the Person You Are

by Toni Morrison

All I had to do for the two dollars was clean Her house for a few hours after school. It was a beautiful house, too, with a plastic-covered sofa and chairs, wall-to-wall blue-and-white carpeting, a white enamel stove, a washing machine and a dryer—things that were common in Her neighborhood, absent in mine. In the middle of the war, She had butter, sugar, steaks, and seam-up-the-back stockings.

I knew how to scrub floors on my knees and how to wash clothes in our zinc tub, but I had never seen a Hoover vacuum cleaner or an iron that wasn’t heated by fire.

Part of my pride in working for Her was earning money I could squander: on movies, candy, paddleballs, jacks, ice-cream cones. But a larger part of my pride was based on the fact that I gave half my wages to my mother, which meant that some of my earnings were used for real things—an insurance-policy payment or what was owed to the milkman or the iceman. The pleasure of being necessary to my parents was profound. I was not like the children in folktales: burdensome mouths to feed, nuisances to be corrected, problems so severe that they were abandoned to the forest. I had a status that doing routine chores in my house did not provide—and it earned me a slow smile, an approving nod from an adult. Confirmations that I was adultlike, not childlike.

I knew how to scrub floors on my knees and how to wash clothes in our zinc tub, but I had never seen a Hoover vacuum cleaner or an iron that wasn’t heated by fire.

Part of my pride in working for Her was earning money I could squander: on movies, candy, paddleballs, jacks, ice-cream cones. But a larger part of my pride was based on the fact that I gave half my wages to my mother, which meant that some of my earnings were used for real things—an insurance-policy payment or what was owed to the milkman or the iceman. The pleasure of being necessary to my parents was profound. I was not like the children in folktales: burdensome mouths to feed, nuisances to be corrected, problems so severe that they were abandoned to the forest. I had a status that doing routine chores in my house did not provide—and it earned me a slow smile, an approving nod from an adult. Confirmations that I was adultlike, not childlike.

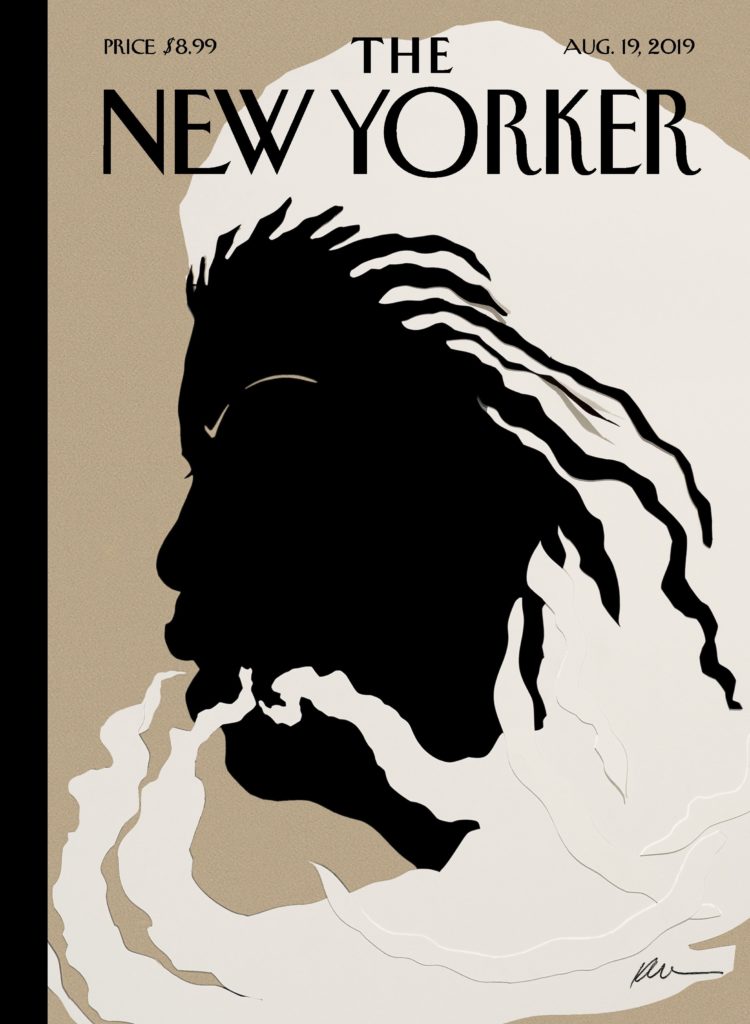

The New Yorker w/ Toni Morrison

Issue: June 5th & 12th 2017

The New Yorker w/ Toni Morrison

Issue: June 5th & 12th 2017

In those days, the forties, children were not just loved or liked; they were needed. They could earn money; they could care for children younger than themselves; they could work the farm, take care of the herd, run errands, and much more. I suspect that children aren’t needed in that way now. They are loved, doted on, protected, and helped. Fine, and yet . . .

Little by little, I got better at cleaning Her house—good enough to be given more to do, much more. I was ordered to carry bookcases upstairs and, once, to move a piano from one side of a room to the other. I fell carrying the bookcases. And after pushing the piano my arms and legs hurt so badly. I wanted to refuse, or at least to complain, but I was afraid She would fire me, and I would lose the freedom the dollar gave me, as well as the standing I had at home—although both were slowly being eroded. She began to offer me her clothes, for a price. Impressed by these worn things, which looked simply gorgeous to a little girl who had only two dresses to wear to school, I bought a few. Until my mother asked me if I really wanted to work for castoffs. So I learned to say “No, thank you” to a faded sweater offered for a quarter of a week’s pay.

Still, I had trouble summoning the courage to discuss or object to the increasing demands She made. And I knew that if I told my mother how unhappy I was she would tell me to quit. Then one day, alone in the kitchen with my father, I let drop a few whines about the job. I gave him details, examples of what troubled me, yet although he listened intently, I saw no sympathy in his eyes. No “Oh, you poor little thing.” Perhaps he understood that what I wanted was a solution to the job, not an escape from it. In any case, he put down his cup of coffee and said, “Listen. You don’t live there. You live here. With your people. Go to work. Get your money. And come on home.”

Little by little, I got better at cleaning Her house—good enough to be given more to do, much more. I was ordered to carry bookcases upstairs and, once, to move a piano from one side of a room to the other. I fell carrying the bookcases. And after pushing the piano my arms and legs hurt so badly. I wanted to refuse, or at least to complain, but I was afraid She would fire me, and I would lose the freedom the dollar gave me, as well as the standing I had at home—although both were slowly being eroded. She began to offer me her clothes, for a price. Impressed by these worn things, which looked simply gorgeous to a little girl who had only two dresses to wear to school, I bought a few. Until my mother asked me if I really wanted to work for castoffs. So I learned to say “No, thank you” to a faded sweater offered for a quarter of a week’s pay.

Still, I had trouble summoning the courage to discuss or object to the increasing demands She made. And I knew that if I told my mother how unhappy I was she would tell me to quit. Then one day, alone in the kitchen with my father, I let drop a few whines about the job. I gave him details, examples of what troubled me, yet although he listened intently, I saw no sympathy in his eyes. No “Oh, you poor little thing.” Perhaps he understood that what I wanted was a solution to the job, not an escape from it. In any case, he put down his cup of coffee and said, “Listen. You don’t live there. You live here. With your people. Go to work. Get your money. And come on home.”